I’ve been spending a lot of time at the Musée Carnavalet of late, and at the risk of hyperbole, it may well be my favorite museum in Paris. Its exhibits portray the history of the city, lingering on its medieval vestiges, the effects of its revolutions, and its many, many, many attempts to revitalize and renew itself.

I love wandering through the rooms decked out in true Art Nouveau fashion, one of which boasts a glitzy bar surrounded by gilded peacocks and stained glass.

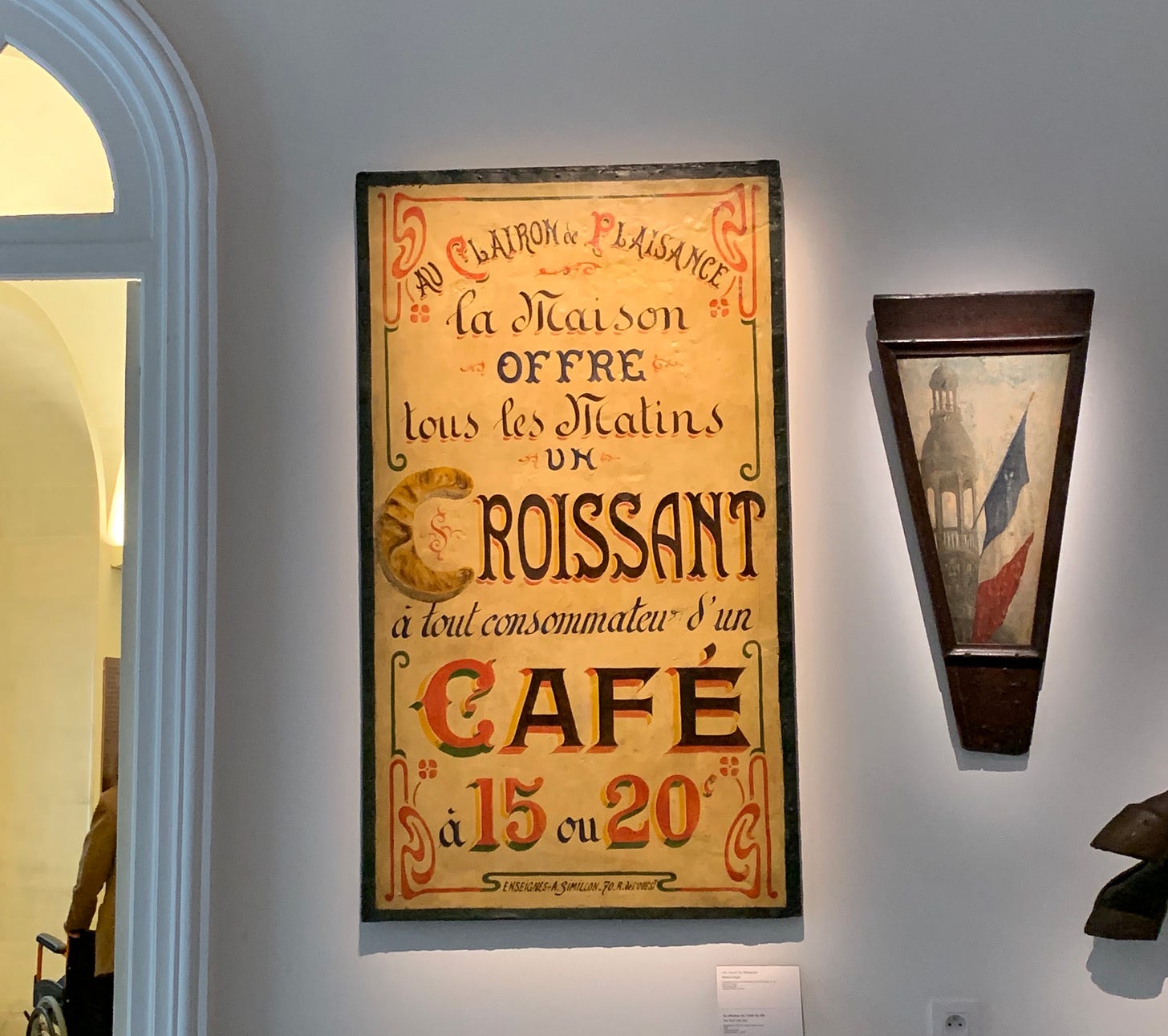

I love the old fashioned signage, from old street signs to placards advertising criminally cheap croissant-café.

But one of my favorite elements of the exhibits are the maps.

For as easy as it is to get pleasantly lost in Paris, it’s a reasonably well-organized city, with wide boulevards, loads of green spaces, and its snail shell of arrondissements beginning with the 1st in the center spiraling out towards the 20th in the northeast. (Paid subscribers have access to my series of guides to a perfect day in each of Paris’ arrondissements; so far I’ve explored the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th).

But in truth, this familiar organization is relatively recent, developed during Napoleon III’s Second Empire, when he tasked Georges-Eugène Haussmann with redesigning the medieval city center. The project stemmed from a multi-pronged goal of providing Paris with drinking water (they didn't call him the aqueduc for nothing), airing out the more cramped areas, where disease ran rampant, and keeping Parisians from throwing up barricades whenever they darn well pleased.

While similarly ambitious plans to circumvent some of these problems had indeed surfaced before, Haussmann’s plan was the first truly successful one. Not only did he create the grande croisée de Paris, a "cross" of the east-west rue de Rivoli and rue Saint-Antoine and north-south boulevards de Strasbourg and de Sébastopol, but he also doubled Paris’ size. On January 1, 1860, Napoléon III officially annexed eleven towns to Paris, including Belleville to the northeast, Passy to the west, and Montmartre to the north – towns that, up until that point, had been considered faubourgs.

The concept of the faubourg has its root in the fact that, for centuries, Paris was a walled city. An original medieval wall was replaced, in 1190, by King Louis-Philippe’s confinement wall, some vestiges of which still remain near the Pantheon, in the Marais, and even in the basement of the Louvre.

The presence of a wall didn't just keep the city safe from Vikings and the English, however. It also drew a very palpable line between those who lived intra muros, within the walls, and those who lived lived directly outside it, particularly around one of the eleven portes piercing it. These villages in close proximity to Paris soon became known as faubourgs: The faubourg Saint-Germain, for example, lay just outside the Parisian neighborhood or bourg of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and the faubourg Saint-Martin, where I live, lay just beyond the reaches of Saint-Martin, in the current Marais.

This little quirk of history is still visible in modern Paris, where any street with faubourg in its name will eventually lead to a street of the same name sans faubourg closer to the historic center. By following the rue du faubourg Saint-Antoine, for example, you’ll eventually reach rue Saint-Antoine.

It was Louis XIV who decided to demolish the confinement wall around Paris and replace it with the Grands Boulevards. But the lack of a wall didn't keep us from continuing to think of Paris as having faubourgs, not just in the names of streets, but also in our conception of what is Paris and what isn't.

In neighborhoods like Montmartre, Belleville, and Butte-aux-Cailles for instance, you’ll find more of a village feel and architecture that stands out from the aptly-named Haussmannien style you find in the rest of Paris. And moreover, even 164 years later, locals of these neighborhoods are fiercely protective of their status, not as Parisians, but as Montmartrois or Bellevilleoise. (If you want to know more about Belleville in particular, may I recommend a tour with my dear friend and Belleville expert Allison Zinder?)

As we come up to the Olympics, the idea of what’s inside Paris and what’s outside of Paris is back on the table. Though our last wall, the Theirs wall, had been completely destroyed by 1929, most Parisians still use the phrase intra muros to describe the city within the péripherique, or ring road surrounding the 20 arrondissements. That said, projects for a Grand Paris have been part of the conversation since 2008, President Nicolas Sarkozy sought to expand the idea of Paris outwards, developing economic poles and better access to public transport in areas that have long been known as the banlieue.

Wikipedia translates both faubourg and banlieue as “suburb,” and while technically I suppose that’s the case, the connotations couldn't be more different. Far beyond the white picket fences and culs de sac the word suburb evokes in English, Paris’ banlieues developed in the post-War ‘50s, when they quickly became home to low-income housing projects. Soon, waves of immigration, particularly from former French colonies, saw these areas essentially ghettoized, and by the ‘70s, the term banlieue had begun to be wielded as shorthand for social disenfranchisement. Many of these towns and cities just outside of Paris remain some of the country's poorest.

When Paris secured the bid to host the Olympics, it was predicated on a regeneration and renewal project focused on Seine-Saint-Denis. The “93,” as it’s called, in the fashion of referring to French departments by their official administrative number, is home to the city of Saint-Denis and the basilica of the same name, the final resting place of 42 French kings, 32 French queens, and 63 princes and princesses. It’s where you’ll find Saint-Ouen’s sprawling flea market and the hipster town of Montreuil, now known for its street art, bars, and music venues.

The 93 is also, essentially, home to the Stade de France and will soon become home to the Olympic village.

The ramifications of hosting the Olympics in Seine-Saint-Denis are, of course, complex. Gentrification in Montreuil specifically has been fiercely criticized, and some Saint-Ouen residents have expressed fears of similar issues in their city as a result of this decision. Other residents are pleased to see their town getting attention, with one lifelong resident telling the Guardian it would be a "showcase" for Saint-Ouen.

Time will tell what the permanent consequences of this choice are, but if nothing else, they are also a keen reminder that Paris’ confines have long been permeable and mutable, and the French capital has always had room to grow.

Cheese of the Week

America’s second-favorite cheese (after mozzarella), cheddar is as varied as it is pervasive, available in forms pasteurized or raw, artisan or industrial. Frankly, I love them all, and if I lived in the UK, a block of mature cheddar from Tesco's would probably be a permanent staple of my fridge.

While these days, cheddar can be made the world over, its roots are in England, and more specifically in Somerset, home to the village that gave the cheese its name. Pitchfork Cheddar stays true to that tradition, handmade and clothbound by Trethowan Brothers, who also make some of the best Caerphilly around. This cheddar is nutty and creamy, with an almost juicy sweetness. Made with the raw milk of Holstein and Jersey cows, it's made according to traditional artisan methods, which include the curds being tossed with a pitchfork-like tool that give the cheese its name.

To discover more of my favorite cheeses, be sure to follow me on Instagram @emily_in_france, subscribe to my YouTube channel, and tune into the Terroir Podcast, where Caroline Conner and I delve into France's cheese, wine, and more one region at a time.

What I’m Eating

Pristine is an insider's spot – but I'm happy to share. I loved so many things about this little restaurant, from the friendly service to the insider’s vibe to the mismatched serving ware to the fact that it’s open on both Sunday and Monday, when most everything is closed. But my favorite thing about it was undoubtedly the creativity coming out of the small open kitchen. More on the blog.

What I’m Doing

1. Our next TERRE/MER retreat is on the books! Join us for cooking, ceramics, and yoga overlooking the Mediterranean from April 11 to 14. Book now to secure yoru spot!

2. Signups for the next edition of the Nantes Writers’ Workshop June 24 to 28 are open! In the meantime, be sure to sign up for our newsletter to keep those creative juices a-flowing.

Where I’m Going

1. To Ashford Castle, to spend some time with my mama and to dine on Chef Liam Finnegan’s ultra-local cuisine in the George V dining room, including honey and ricotta produced on the grounds of the nearly 800-year-old castle.

2. To Dublin's Dax, a modern Franco-Irish fine dining spot in the Georgian district.

3. To the Salon de l’Agriculture, and more specifically to the Salon du Fromage, where I’ll be judging the national dairy products contest.

What I'm Writing

1. Whether it's a classic French béarnaise or a house-made chili paste, the perfect sauce often adds just the right allure to a dish. And while sauces are time-tested, pervasive favorites, we're seeing even of them these days, according to Maxime Bouttier, chef-owner of Paris' Géosmine, due to rising trends in highlighting an ingredient in all its simplicity. In this case, he says, "What brings the products together is the sauce." For Mashed.

2. Cereal sales are down, but these childhood faves are all over cocktail menus. I explore this trend for InsideHook.

3. From the archives: Here's what it's like to judge the Oscars of cheese. For InsideHook.

What I'm Reading

1. Emile Chabal’s pocket-sized France is positively brimming with excellent analysis of what makes the French tick. Predicated on the innate paradoxes of France and the French, it explores France's chief values in six distinct chapters, digging deep into the history, for example, of the right-left divide, the illusion of grandeur Charles de Gaulle sought to project in a post-World War world, or the importance of republicanism, while also threading in modern political and social analysis of the ways in which France is changing in an ever-globalizing world. A must-read for anyone who is curious about why the French are the way they are.

2. This story about the victory of the bouquinnistes over bureaucracy… with one of the most delightfully French conclusions I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading. In the New York Times.

3. This tip on pairing cheese with coffee, suggesting double or triple cream cheeses. (I personally loved Maroilles with coffee, but to each his own.) In Tasting Table.

A bientôt !